See, It's Just a Game

Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan write an IllAdvised Opinion about an innocent person that the Supreme Court left in Jail because... rules.

Proverbs 31:9 Open thy mouth, judge righteously, and plead the cause of the poor and needy.

So what happens when you’ve used up your appeals and there is a change in the meaning of the law…? Well, if its all a game they leave you in jail.

The situation is this: A prisoner was jailed for violating a law. The rules for violating that law did not include, at the time, mens rea (about which I have commented). Later the Supreme Court said that you did need to include mens rea in applying that law. In other words, the Supreme Court gave a small nod to the idea that you do have to have some idea of what the law is that you are said to be violating.

So a prisoner who had been jailed prior to this decision filed an appeal. But because this prisoner had already used up his appeal… he’s out of luck. You can’t get clearer than this: they are treating this like a game. Another prisoner, with the exact same facts, who hadn’t used up his appeal would (assuming the facts are correct) get out of jail. IOW if you had had a lazier attorney, or been convicted more recently, or just hadn’t thought of anything to appeal… you would be out.

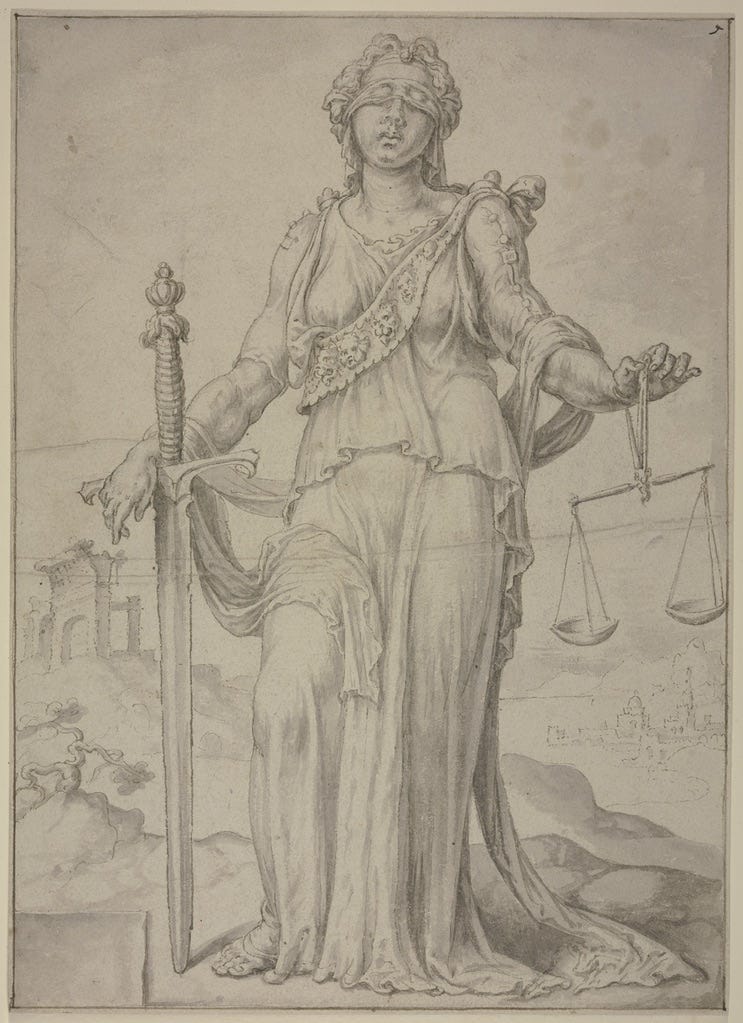

Justice should not be a game. Yes, we have to have rules, but in the end the rules have to serve the cause of justice. And you should never, ever be able to get to the point where you say, “Yes, you are innocent, but according to the rules…”

Dissent

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

_________________

No. 21–857

_________________

MARCUS DEANGELO JONES, PETITIONER v. DEWAYNE HENDRIX, WARDEN

on writ of certiorari to the united states court of appeals for the eighth circuit

[June 22, 2023]

Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan, dissenting.

We respectfully dissent. As Justice Jackson explains, today’s decision yields disturbing results. See post, at 23–25 (dissenting opinion). A prisoner who is actually innocent, imprisoned for conduct that Congress did not criminalize, is forever barred by 28 U. S. C. §2255(h) from raising that claim, merely because he previously sought postconviction relief. It does not matter that an intervening decision of this Court confirms his innocence. By challenging his conviction once before, he forfeited his freedom.

Though we agree with Justice Jackson that this is not the scheme Congress designed, we see the matter as the Solicitor General does. As all agree, Congress enacted §2255 to “afford federal prisoners a remedy identical in scope to federal habeas corpus.” Davis v. United States, 417 U. S. 333, 343 (1974). To ensure that equivalence, Congress built in a saving clause, allowing recourse to habeas when the “remedy by motion” under §2255 is “inadequate or ineffective” compared to the remedy it replaced: an “application for a writ of habeas corpus.” §2255(e). So, as this Court has explained, if §2255 bars a claim cognizable at habeas, such that the remedies are not “commensurate,” the saving clause kicks in, and the prisoner may “proceed in federal habeas corpus.” Sanders v. United States, 373 U. S. 1, 14–15 (1963); see United States v. Hayman, 342 U. S. 205, 223 (1952).

With that understanding in mind, consider a prisoner who, having already filed a motion for postconviction relief, discovers that a new decision of this Court establishes that his statute of conviction did not cover his conduct. He is out of luck under §2255, because §2255(h) will bar his claim. But that claim is cognizable at habeas, where we have long held that federal prisoners can collaterally attack their convictions in successive petitions if they can make a colorable showing that they are innocent under an intervening decision of statutory construction. See Davis, 417 U. S., at 344–347; McCleskey v. Zant, 499 U. S. 467, 493–495 (1991). Congress did not abrogate that principle in §2255(h). Thus, we have precisely the kind of mismatch the saving clause was designed to address.

In this case, the petitioner says he is that prisoner, with that mismatch. But the Court of Appeals never considered that question, laboring under a mistaken view of the saving clause that, like the majority’s, assigns it almost no role. Accordingly, we would remand for the lower courts to consider the petitioner’s claim under the proper framework. See Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U. S. 709, 718, n. 7 (2005).

(I love comments, particularly intelligent comments that disagree)