The modern man looking at the most ancient origins has been like a man watching for daybreak in a strange land; and expecting to see that dawn breaking behind bare uplands or solitary peaks. But that dawn is breaking behind the black bulk of great cities long builded and lost for us in the original night; colossal cities like the houses of giants, in which even the carved ornamental animals are taller than the palm-trees; in which the painted portrait can be twelve times the size of the man; with tombs like mountains of man set four-square and pointing to the stars; with winged and bearded bulls standing and staring enormous at the gates of temples; standing still eternally as if a stamp would shake the world. The dawn of history reveals a humanity already civilised. Perhaps it reveals a civilisation already old. And among other more important things, it reveals the folly of most of the generalisations about the previous and unknown period when it was really young. The two first human societies of which we have any reliable and detailed record are Babylon and Egypt. It so happens that these two vast and splendid achievements of the genius of the ancients bear witness against two of the commonest and crudest assumptions of the culture of the moderns. If we want to get rid of half the nonsense about nomads and cave-men and the old man of the forest, we need only look steadily at the two solid and stupendous facts called Egypt and Babylon.

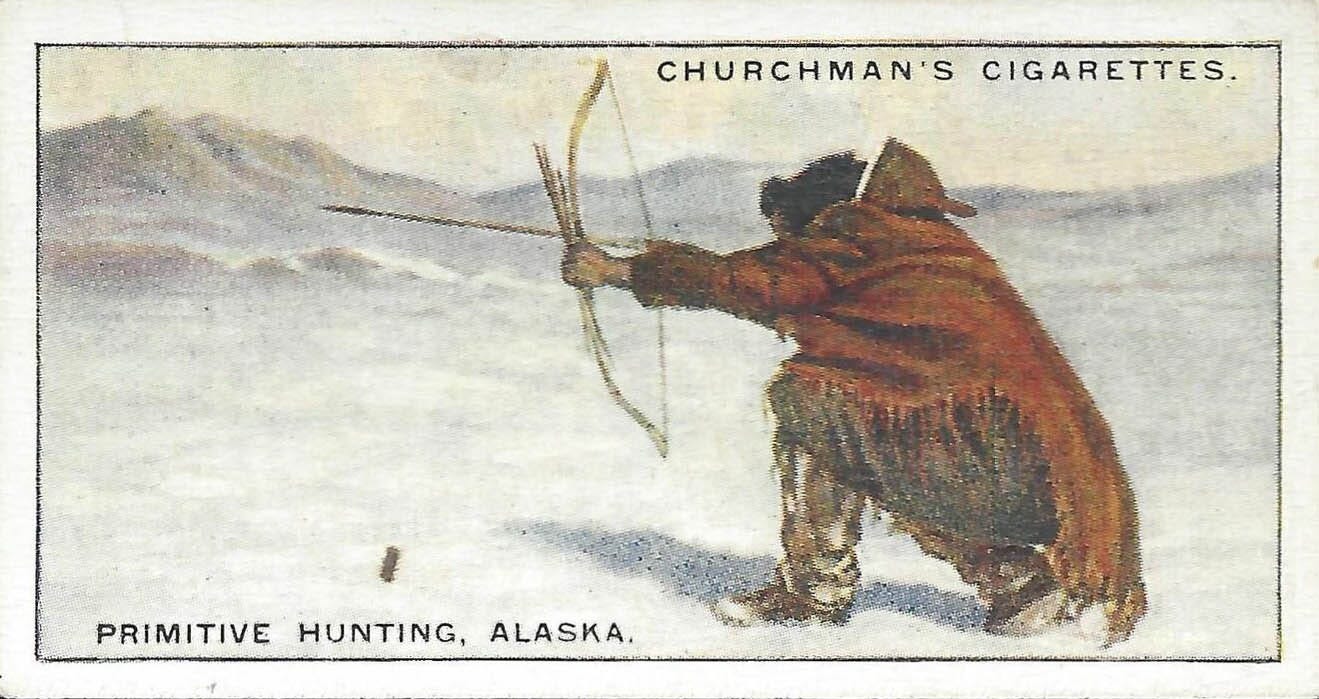

Of course most of these speculators who are talking about primitive men are thinking about modern savages. They prove their progressive evolution by assuming that a great part of the human race has not progressed or evolved; or even changed in any way at all. I do not agree with their theory of change; nor do I agree with their dogma of things unchangeable. I may not believe that civilised man has had so rapid and recent a progress; but I cannot quite understand why uncivilised man should be so mystically immortal and immutable. A somewhat simpler mode of thought and speech seems to me to be needed throughout this inquiry. Modern savages cannot be exactly like primitive man, because they are not primitive. Modern savages are not ancient because they are modern. Something has happened to their race as much as to ours, during the thousands of years of our existence and endurance on the earth. They have had some experiences, and have presumably acted on them if not profited by them, like the rest of us. They have had some environment, and even some change of environment, and have presumably adapted themselves to it in a proper and decorous evolutionary manner. This would be true even if the experiences were mild or the environment dreary; for there is an effect in mere time when it takes the moral form of monotony. But it has appeared to a good many intelligent and well-informed people quite as probable that the experience of the savages has been that of a decline from civilisation. Most of those who criticise this view do not seem to have any very clear notion of what a decline from civilisation would be like. Heaven help them, it is likely enough that they will soon find out. They seem to be content if cave-men and cannibal islanders have some things in common, such as certain particular implements. But it is obvious on the face of it that any peoples reduced for any reason to a ruder life would have some things in common. If we lost all our firearms we should{60} make bows and arrows; but we should not necessarily resemble in every way the first men who made bows and arrows. It is said that the Russians in their great retreat were so short of armament that they fought with clubs cut in the wood. But a professor of the future would err in supposing that the Russian Army of 1916 was a naked Scythian tribe that had never been out of the wood. It is like saying that a man in his second childhood must exactly copy his first. A baby is bald like an old man; but it would be an error for one ignorant of infancy to infer that the baby had a long white beard. Both a baby and an old man walk with difficulty; but he who shall expect the old gentleman to lie on his back, and kick joyfully instead, will be disappointed.

It is therefore absurd to argue that the first pioneers of humanity must have been identical with some of the last and most stagnant leavings of it. There were almost certainly some things, there were probably many things, in which the two were widely different or flatly contrary. An example of the way in which this distinction works, and an example essential to our argument here, is that of the nature and origin of government. I have already alluded to Mr. H. G. Wells and the Old Man, with whom he appears to be on such intimate terms. If we considered the cold facts of prehistoric evidence for this portrait of the prehistoric chief of the tribe, we could only excuse it by saying that its brilliant and versatile author simply forgot for a moment that he was supposed to be writing a history, and dreamed he was writing one of his own very wonderful and imaginative romances. At least I cannot imagine how he can possibly know that the prehistoric ruler was called the Old Man or that court etiquette requires it to be spelt with capital letters. He says of the same potentate, ‘No one was allowed to touch his spear or to sit in his seat.’ I have difficulty in believing that anybody{61} has dug up a prehistoric spear with a prehistoric label, ‘Visitors are Requested not to Touch,’ or a complete throne with the inscription, ‘Reserved for the Old Man.’ But it may be presumed that the writer, who can hardly be supposed to be merely making up things out of his own head, was merely taking for granted this very dubious parallel between the prehistoric and the decivilised man. It may be that in certain savage tribes the chief is called the Old Man and nobody is allowed to touch his spear or sit on his seat. It may be that in those cases he is surrounded with superstitious and traditional terrors; and it may be that in those cases, for all I know, he is despotic and tyrannical. But there is not a grain of evidence that primitive government was despotic and tyrannical. It may have been, of course, for it may have been anything or even nothing; it may not have existed at all. But the despotism in certain dingy and decayed tribes in the twentieth century does not prove that the first men were ruled despotically. It does not even suggest it; it does not even begin to hint at it. If there is one fact we really can prove, from the history that we really do know, it is that despotism can be a development, often a late development and very often indeed the end of societies that have been highly democratic. A despotism may almost be defined as a tired democracy. As fatigue falls on a community, the citizens are less inclined for that eternal vigilance which has truly been called the price of liberty; and they prefer to arm only one single sentinel to watch the city while they sleep. It is also true that they sometimes needed him for some sudden and militant act of reform; it is equally true that he often took advantage of being the strong man armed to be a tyrant like some of the Sultans of the East. But I cannot see why the Sultan should have appeared any earlier in history than many other human figures. On the contrary, the strong man armed obviously depends upon the superiority of his armour; and armament of that sort comes with more complex civilisation. One man may kill twenty with a machine-gun; it is obviously less likely that he could do it with a piece of flint. As for the current cant about the strongest man ruling by force and fear, it is simply a nursery fairy-tale about a giant with a hundred hands. Twenty men could hold down the strongest strong man in any society, ancient or modern. Undoubtedly they might admire, in a romantic and poetical sense, the man who was really the strongest; but that is quite a different thing, and is as purely moral and even mystical as the admiration for the purest or the wisest. But the spirit that endures the mere cruelties and caprices of an established despot is the spirit of an ancient and settled and probably stiffened society, not the spirit of a new one. As his name implies, the Old Man is the ruler of an old humanity.

It is far more probable that a primitive society was something like a pure democracy. To this day the comparatively simple agricultural communities are by far the purest democracies. Democracy is a thing which is always breaking down through the complexity of civilisation. Any one who likes may state it by saying that democracy is the foe of civilisation. But he must remember that some of us really prefer democracy to civilisation, in the sense of preferring democracy to complexity. Anyhow, peasants tilling patches of their own land in a rough equality, and meeting to vote directly under a village tree, are the most truly self-governing of men. It is surely as likely as not that such a simple idea was found in the first condition of even simpler men. Indeed the despotic vision is exaggerated, even if we do not regard the men as men. Even on an evolutionary assumption of the most materialistic sort, there is really no reason why men should not have had at least as much camaraderie as rats or rooks. Leader{63}ship of some sort they doubtless had, as have the gregarious animals; but leadership implies no such irrational servility as that attributed to the superstitious subjects of the Old Man. There was doubtless somebody corresponding, to use Tennyson’s expression, to the many-wintered crow that leads the clanging rookery home. But I fancy that if that venerable fowl began to act after the fashion of some Sultans in ancient and decayed Asia, it would become a very clanging rookery and the many-wintered crow would not see many more winters. It may be remarked, in this connection, but even among animals it would seem that something else is respected more than bestial violence, if it be only the familiarity which in men is called tradition or the experience which in men is called wisdom. I do not know if crows really follow the oldest crow, but if they do they are certainly not following the strongest crow. And I do know, in the human case, that if some ritual of seniority keeps savages reverencing somebody called the Old Man, then at least they have not our own servile sentimental weakness for worshipping the Strong Man.

Thank you for reading Von’s Substack. I would love it if you commented! I love hearing from readers, especially critical comments. I would love to start more letter exchanges, so if there’s a subject you’re interested in, get writing and tag me!

Being ‘restacked’ and mentioned in ‘notes’ is very important for lesser-known stacks so… feel free! I’m semi-retired and write as a ministry (and for fun) so you don’t need to feel guilty you aren’t paying for anything, but if you enjoy my writing (even if you dramatically disagree with it), then restack, please! Or mention me in one of your own posts.

If I don’t write you back it is almost certain that I didn’t see it, so please feel free to comment and link to your post. Or if you just think I would be interested in your post!

Thanks again, God Bless, Soli Deo gloria,

Von

Quotes

A bunch of fun and significant quotes:

John Taylor Gatto #1

John Taylor Gatto #2

John Taylor Gatto #3

Education Quotes #2

Education Quotes #1

Chesterton

A Folly of Socialism

The Fire and the Wife

Ignorance Covered with Impudence

Is there only One Party?

The Feminine Ideal

The Long Word // Podcast Version

The Caveman and the Club // Podcast Version

The Walls of the Cave // Podcast Version

The Plain Truth // Podcast Version

The Emancipation of Domesticity // Podcast Version

The Romance of Thrift // Podcast Version

CS Lewis

Men Without Chests

High Ideals // Podcast VersionPoems

Posting and analysing some important poems.